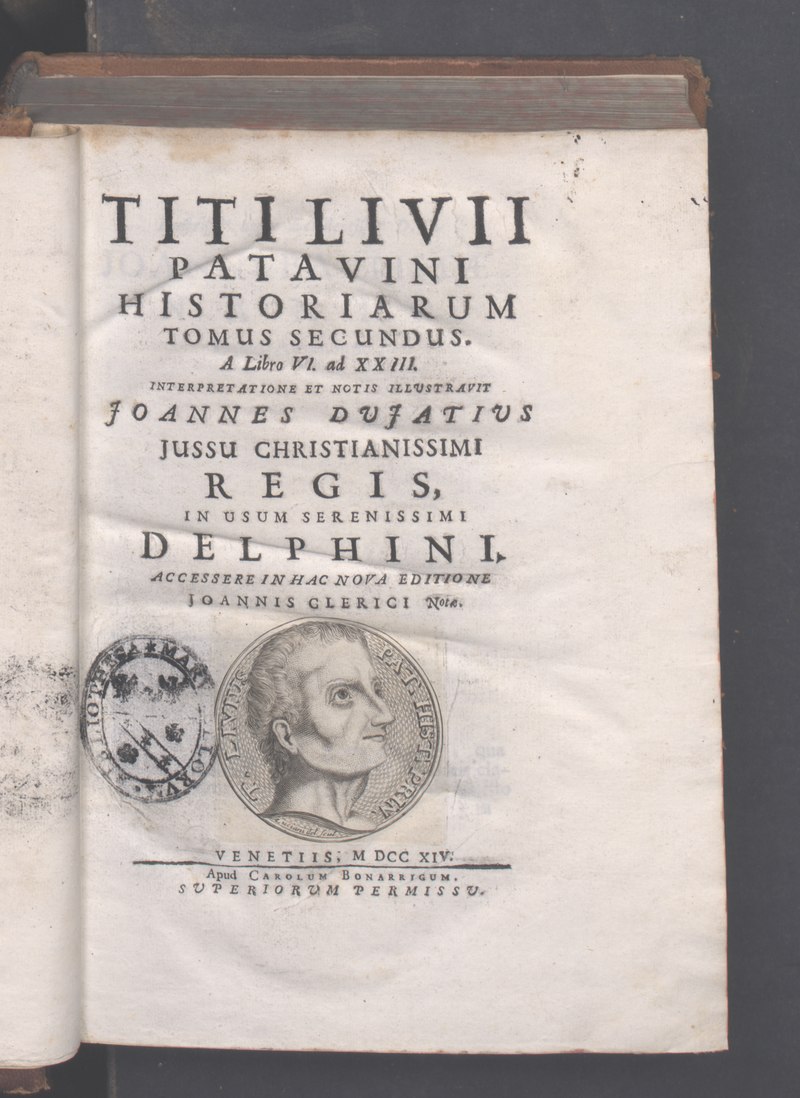

Two thousand years ago Titus Livius, in his History of Rome, declared that his book, indeed any narrative history of human events told with empathy and truth, is therapy for mental malaise, especially the malaise that is a product of conspicuous consumption, avarice, lust, fear, violence, narcissism, and all of the other sins that beset humankind. History is therapeutic, Livy argued, because its study is the means by which a person can find the good in past human behavior to imitate, and discover the evil in past human behavior to avoid. History provides a didactic purpose of moral reform.

Does it still? Is this still the point behind historical inquiry, to educate people in moral behavior, to teach them how to act, how to achieve contentment? I wonder . . . especially in our age of cultural and moral relativism, where “anything goes” seems to be the moral prerogative of people—as long as one’s behavior does not apparently hurt anyone else (no matter what it does to the self), then the behavior is acceptable

One argument against didacticism in historical study is that there is no longer a recognized universal moral system that unites people of such diverse cultural, ethnic, racial, religious, and philosophical backgrounds. Narrative history such as Livy wrote tends to reflect the worldview of the writer who typically represents the majority view of the time, leaving out the cultural, ethnic, and racial minorities.

Livy wrote, however, during a golden age of historical inquiry, when the likes of Tacitus and Plutarch wrote. Plutarch, the author of Lives and Moralia, believed that the historian/biographer should treat the past like a person inviting a guest to visit; Plutarch would settle down to his writing desk and, looking through the writings of Caesar (for example), invite the Roman general and writer, as it were, to sit down with him, and vicariously discuss the issues and ideas of his time. This dialogue with a person of the past allowed Plutarch to build an intellectual and empathetic connection with the past person, which allowed the subject and object (Plutarch and Caesar in this case), to join together, seeing what united them, what divided them, and discovering the common human experiences, feelings, and thoughts that bridge time and place.

The dialogue with the past is the didactic purpose behind historical inquiry that I seek to reproduce and engender in my writing. This is the kind of moral history that I believe in. When two humans—and many more—join together in a dialogue, enabled by surviving historical sources, joining feelings and thoughts together, then I believe the historian and his/her readers discover what is universally true in human affairs, and yes, as Livy would have it, what is the good to imitate, and what is the evil to avoid.

Great article!

Thanks!