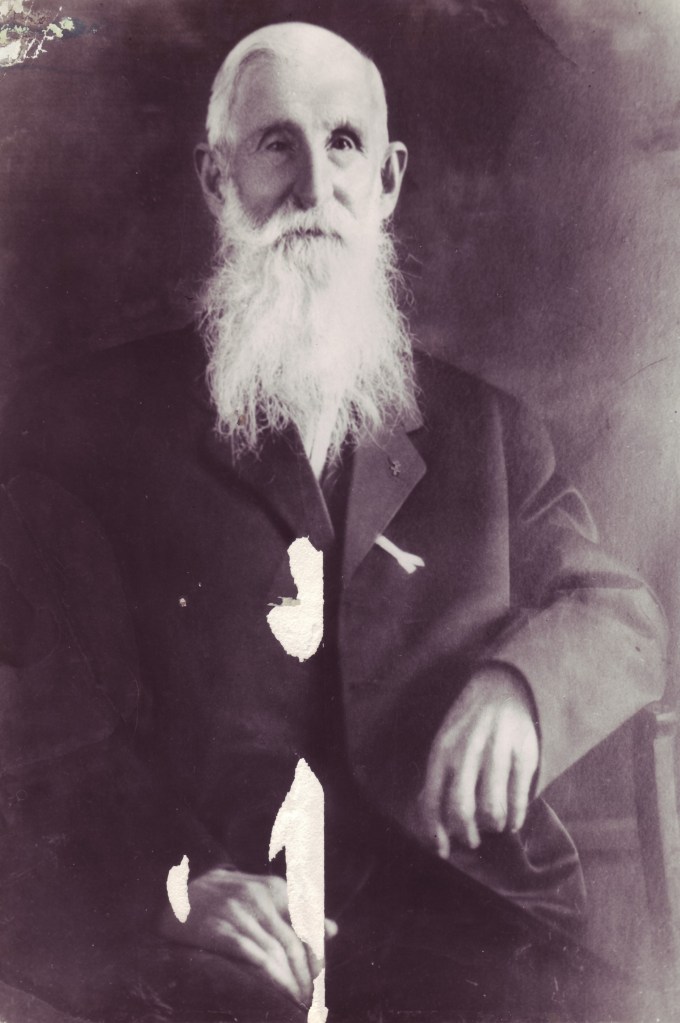

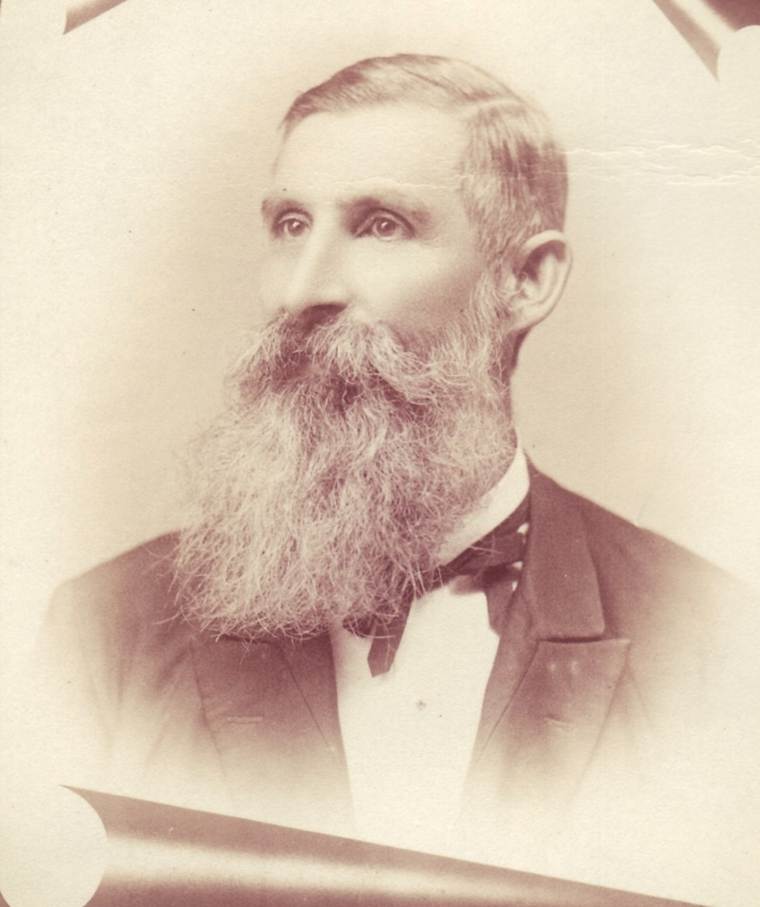

Joseph Murrow was a Southern Baptist Missionary who spent much of his life working among the American Indians of Oklahoma, bringing Christianity to people throughout Oklahoma and Indian Territory and the State of Oklahoma.

Murrow first came to Indian Territory in 1857 when he was twenty-two years old. He arrived at North Fork Town, near Eufaula, in November, and immediately met with the Creek Indians. In Murrow’s first sermon to the Creeks he spoke words that would become his motto for life: “For I seek not yours but you.” This white man from Georgia did not come among them to take, but to give, not to acquire their land, but to acquire their love in giving the message of Jesus Christ. And he was successful. Murrow was apologetic for what the Indians had suffered, determined that he would help them recover, that he would not contribute to the crimes committed by Whites against the Indians.

Murrow’s eyes were immediately opened to the spirit and ways of these people, their inherent goodness and desire to embrace the truth. “It seems to me that here,” he wrote in December, 1857, “if anywhere in the world, is god worshipped in spirit and in truth.” The Indians were sincere in their religious affectations. “These Indians do everything in the spirit. They sing in the spirit. . . . They pray in the spirit, too.” They welcomed Murrow and his new wife so unreservedly, that “our souls were almost lifted out of the poor mortal clay. Mrs. Murrow was almost overcome. I just felt that if my work had even then been finished that I would have been richly repaid for all the sacrifices which I had made in coming out here.” But his work was not finished, and would continue for over seventy years.

During his brief time with the Creeks, Murrow’s wife and first child died, and he was very ill; he remarried and decided to move further west to minister to the Seminoles, arriving in 1860. When the Civil War began, and throughout the war, Murrow stayed with the Seminoles, ministering to their needs, supporting their decision to support the Confederacy, as most Indians of Indian Territory did. Murrow was one of the few Baptist missionaries who stayed and worked in Indian Territory during the war. At the end of the war, Indian Territory was largely devastated, and half the lands of the Five Civilized tribes were taken by the United States government. Murrow discovered that the Choctaw Nation needed the services of a missionary, so he moved to the Choctaw town of Boggy Depot, then founded the town of Atoka, where he resided for the rest of his life. Murrow founded the Atoka Baptist Church, and outlived many children and four wives. He became very involved in helping to establish and organize Indian Baptist associations, such as the Choctaw-Chickasaw Association. The Rehoboth Association of the Southern Baptists supported Murrow’s missionary work for many years, replaced in the 1880s by the Home Mission Board of the Southern Baptist Convention.

During the 1880s and 1890s, however, a dispute arose in Indian Territory between the Home Mission Board of the Southern Baptist Convention and the American Baptist Home Mission Society, centered in New York City. The split in the Baptists of America dated back to the sectional rift over slavery in the years before the Civil War. Murrow was involved in many religious political disputes as he tried to serve at the same time the Southern Baptists and the American Baptists. Murrow joined with the American Baptists Daniel Rogers and Almon C. Bacone in founding Indian University (Bacone College). The Southern Baptist Murrow was the first President of the Board of Trustees of Indian University, and continued in that position for many years, even as Indian University was founded, funded, and essentially controlled by the American Baptist Home Mission Board. His concern was not religious politics but the Great Commission. Murrow believed it was absolutely necessary to continue Almon Bacone’s dream of Indian University existing to mark the Jesus Road for Indians.

Joseph Murrow had a dream. He dreamed (as he recorded it in 1913) that there was “a man standing on a high hill, looking intently over the landscape, far and near.” Murrow approached the man and discovered that he was “a well-known Indian, of strong character, with a broad, far-seeing outlook, whose influence among his people was great.” The time of the dream was a few years after the Civil War, which had devastated Indian Territory. The Indian bemoaned “the condition of his people and his country; his country being laid waste . . . , and his people homeless.” In the dream, a white man from Georgia approached, greeted the Indian, and made a speech in which he apologized for the actions of white people in driving the Five Civilized tribes from the homeland in the East. He claimed that God had punished the Southerners for their ill treatment of the Indians by destroying the South in the Civil War. He said that Whites were fleeing the destruction, moving West, hoping to find homes in Indian Territory, and wished the Indian to know that they were apologetic, and wished to be forgiven and embraced so that White and Indian could work together to thrive in the new land. Another white man approached, and he said he was a sojourner from Missouri, that he was looking for a new place, and that he promised, if allowed to settle there, to treat the Indians fairly.

In Murrow’s dream the Indian listened to the speeches, then replied that he was “greatly astonished at what you have said,” that most Whites lie, but these men appear to speak the truth, and to be sincerely sorry for their actions. He realized that the Indians needed the help of the white man to thrive, that they wished for the blessings of Christianity and that “all the tribes would become Christians if they had an opportunity.” At the same time, he recalled the past, he recalled how his people had once lived among Christians and yet they “were treated almost like dogs” by the Whites. “They were not allowed to enter the schools, nor the churches, nor other public places, not even the dwelling houses of your people.” Yet the Indian believed that if all Whites were as sincere as these two men, that Indians and Whites could indeed live together in peace.

Soon, in the dream, another white man approached, this one from New England. He professed his belief in God, his agreement with what the others had said, and his desire to bring money from the North to help the impoverished Southerners and Indians to live together in harmony. Then, strangely, another white man approached, who proclaimed he was “a commissioner or official from Washington City.” He agreed with all that had been said, and wanted to pledge to the Indians that the United States government would henceforth treat them fairly, and respect all treaties, even those that had been previously broken.

Murrow, in his dream, had been an observer of all that had been said, and when he saw that Whites from the South and the North, even the United States government, were now going to work to help the Indian, bring Christianity to him, and treat him fairly, he cried out “Hallelujah”!

Murrow “awoke, and behold it was a dream. ‘Of all sad words of tongue or pen, The saddest are these, It might have been’.”

It might have been, but it was not. What was this nightmare that Murrow faced when he awoke? It was a nightmare of unfulfilled promises, of the loss of faith, of the work of years allowed to slip away, of continuing abuse, of ongoing exploitation.

Murrow founded the orphanage in 1902 to help Indian children who were increasingly prey to unscrupulous extortionists seeking to take legal control of lands allotted to the parent-less. “True, they have land,” Murrow told his daughter Clara McBride, “but it is universally and lamentably true that they can neither eat nor wear their land and that unless some one personally interested in these children has charge of their allotment, their fate is invariably a hard one.” The allotment of individual Indian’s land (usually 160 acres) often helped support an independent and progressive lifestyle, especially of a person who was ready and willing to assume such responsibility. On the other hand, allotting land to youngsters who did not have the slightest idea what to do with it, especially if the land was productive or had mineral wealth, could become a ripe occasion for various forms of exploitation. The land-shark, or better, leech, “which goes upon two legs, and takes the form of a white man, . . . is found quietly waiting on the verge or in the midst of every business center frequented by . . . Indians.” The land leech “wins the good will of the Indian by helping him with the loan of a small amount of money when the Indian is in need.” One young Indian orphan, “after she became of legal age,” visited relatives and friends “and was inveigled into signing a deed for a piece of property, at a price not half what it was worth, and when the deed was made out it covered twice the amount of land sold. The girl did not understand the description and so was ignorant of its import. The deed was, however, properly signed and witnessed and so must . . . stand.” Orphans who had lost their land by these means were the object of Murrow’s benevolence. Murrow asked “that they be gathered into a home, on a farm, and taught habits of industry and thrift, taught moral Christian principles, given a common school education and thus saved from ignorance and indolence, a burden and menace to society, and trained to become productive citizens.” This was the aim of the Murrow Indian Orphans’ Home initially in Atoka, and after 1910, at Bacone College.

Murrow in 1903 launched a newsletter, The Indian Orphan, to attract attention to the Orphans’ Home; when control of the home passed to Bacone College in 1910, so did responsibility to publish the newsletter. The October, 1910, issue of the Indian Orphan explained the reasoning behind relocating the Orphans’ Home: “Here we had a school founded for the Indian, a school of such grade as would provide opportunity for our children to continue their education on through the academy and the college course if inclination so directed. Here we had land sufficient to carry on all the operations of practical farm work. . . . The college could help the Home by furnishing trained teachers in agriculture, manual training and domestic science, . . . ; and in return The [Orphans’] Home would naturally become the feeder of the college by furnishing it pupils from its upper classes.”

Murrow was a great support to Indian University/Bacone College during the first fifty years of its founding and growth. He worked closely with Almon Bacone and Benjamin Weeks, two of the most important presidents of the college. Murrow declared Weeks to be “God appointed”—“an excellent President. He has the confidence of all the Indians and of all his workers and pupils.” Murrow, a dedicated Mason, would be hard put to give up on a brother who was “a thirty-second degree Mason,” very accomplished in the order, given to charitable works.

When Murrow met with the Kiowas, Comanches, and Apaches; “the strongest of the chiefs, Lone Wolf (Kiowa) came to Father Murrow and asked that some one be sent to teach them the New Trail,” the Jesus Road. Murrow returned with two missionaries, Miss Reside and Miss Ballew; Murrow “requested that the Indians give protection to the women who had come to teach them. Lone Wolf answered by drawing three circles. He asked the missionaries to stand in the first circle. Big Tree, Stumbling Bear and Lone Wolf stood in the second. In one still larger, the rest of the Indians were placed. Thus surrounding the women the Indians pledged loyalty and security.”

Among Indian children, Murrow was known as Father Row; among adults, he was Father Murrow. His useful and long life came to an end in 1929.

The above narrative is taken from Marking the Jesus Road: Bacone College through the Years, newly republished in January 2026 and available on Amazon at Marking the Jesus Road: Bacone College through the Years: Lawson, Dr. Russell Matthew: 9780977244805: Amazon.com: Books